Five pointers for the proposed US-Ukraine critical minerals deal from other natural resource agreements in unstable regions.

By Daniel Litvin*

5th March 2025

*Please note this article expresses the author’s personal views and not necessarily the views of others associated with Resource Resolutions

Several days after the blazing Oval Office row between Presidents Trump and Zelensky, the much-heralded ‘critical minerals’ deal between the US and Ukraine seems to be on the cards again – at least at the timing of writing. President Zelensky says he is ready to sign. President Trump remains interested.

If the deal is to go ahead, there are some basic lessons to be drawn from other agreements over resources in other challenging parts of the world. These should certainly inform its implementation.

These high-level observations are drawn from my 20-or-so years of experience analysing and advising on such resource deals and projects, supplemented by insights from my RR colleagues. None of these projects were as headline-grabbing as the US-Ukraine deal, but many of the underlying patterns and themes are identical.

Put simply, striking an agreement over natural resources which proves genuinely ‘win-win’ over the long term requires a holistic, strategic, sober and sensitive approach. The current US-Ukraine deal has much to prove in this respect.

The architects of any such deal, we would argue, need to:

1. Build a joint fact base rooted in technical expertise, not inflated expectations.

Expert opinion suggests the US-Ukraine deal, as originally articulated, was based on wildly overblown claims about the extent and value of Ukraine’s critical mineral resources. This may have been intentional: to impress domestic US audiences. It may also have been due to misunderstanding of industry basics (for example the difference between mineral resources – the estimated overall quantity of raw materials under the ground – and mineral reserves – the smaller proportion it makes economic sense to dig up.) Limited understanding of the timelines and technical risks associated with bringing rare earths and other critical minerals into development likely also gave a misleading impression as to when the US might begin to benefit from the deal.

Whatever the reason for the misapprehension, inflated expectations of benefits from resource deals have often been a cause of their unravelling over the long term. As reality dawns, parties feel cheated and seek to reclaim what they feel is owed. In countless cases, governments of mineral-rich countries, local communities around mines, and sometimes investors, have claimed to have been misled by mining companies who seemed to be promising great riches, leading to disputes and sometime outright conflict (see here and here and here for examples).

With public understanding of geology and resource economics limited, the mining industry is prone to overblown claims gaining popular traction. As Mark Twain is said to have quipped about mining, “the definition of a mine is ‘a hole in the ground with a liar at the top.’” From the perspective of the US-Ukraine deal, a period of sober, joint fact-finding seems an important next step to set a stronger basis for constructive collaboration in the months ahead.

2. Avoid getting hung up on minerals under the ground: focus on the broader minerals value chain.

The talk around the US-Ukraine deal so far has focused mostly on the potential profits from extracting the critical minerals under Ukraine’s soil. Such talk distracts from what is arguably a far bigger economic and security prize: the processing and refining of these minerals and their application in the manufacture of strategically important industrial components and products (such as batteries).

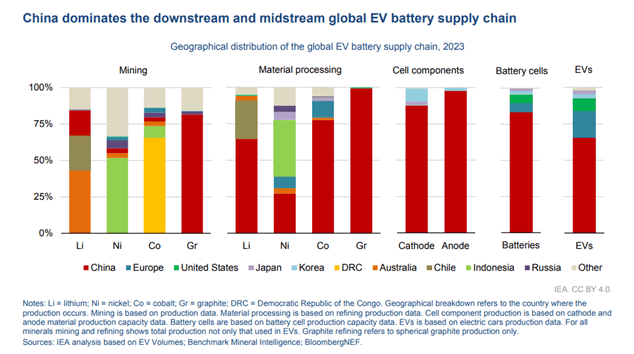

A big motivation for the US’ current interest in Ukraine’s resources is fear of Chinese dominance of the global value chains associated with critical minerals. But this Chinese dominance occurs more starkly in the refining and manufacturing segments of these value chains than in the actual mining of critical minerals (see chart below – the red denotes China). Put another way, even if the US came to control extraction of all Ukraine’s critical minerals, this in itself would do little to tackle the main strategic challenge in this area for the US.

Source: IEA Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024, page 30: Link here

This excessive focus on extraction reflects a common pattern in the politics of resources. Throughout history, major resource deposits have regularly attracted the attention of competing groups, each seeking to dominate and capture the profits that come from extraction. Meanwhile, fewer energies are devoted to devising collaborative approaches that might grow the value chain from using the resource concerned, even though the size of the prize here could be of a different scale. Ultimately this is a harder task, requiring long term vision, trust and strong institutions. Parties end up squabbling over a small pie, rather than jointly baking a giant one.

A tragic, current example of this is the Democratic Republic of Congo, a mineral-rich country long riven by conflicts over control of extraction. A counterexample from history is the UK and its coal reserves. Britain leveraged these reserves to become the dominant global economic power in the nineteenth century, but less due to the profits from coal extraction, and more due to the industrial value chains it built upon them. Today, a giant prize is available to both Washington and Kyiv if Ukraine’s critical minerals can be similarly leveraged. This is where the next stages of discussion over their deal might be most usefully focused.

3. Understand that self-interest is served by a deal seen to be fair rather than unbalanced.

As first reported, the proposed US-Ukraine deal seemed to many observers (certainly those in Ukraine) as deeply unbalanced in the US’s favour. The US wants repayment from Ukraine for billions of dollars of past military support and was viewing critical minerals as a means to that end. Later reported iterations of the proposed deal appeared to leave open more room for mutual advantage. A joint fund is to be established in which profits from Ukraine’s resources, while now partly controlled by the US, are to be reinvested to “promote the safety, security and prosperity of Ukraine”. To ensure the deal is truly sustainable from both parties’ perspective, this more tempered approach will likely need more development and elaboration.

The history of big resource deals elsewhere in the world is again littered with examples of agreements sooner or later rewritten, or ripped up without compensation, as host countries and populations turn against foreign entities they view (fairly or not) as profiting excessively. Against such tides of popular resentment, contracts and legal defences often count for little.

During 1960s and 70s, for example, a series of giant western oil concessions in the Middle East were successively revised and then effectively cancelled as countries in the region turned against foreign companies and powers they perceived to be ripping them off. This dealt a lasting blow to US and western energy security. In recent years, few major foreign-owned mining projects in developing countries have escaped periodic surges of such ‘resource nationalism’, with some foreign miners only clinging on by their fingernails (see here, here, and here for example). Today in Ukraine, the US would appear to have the upper hand in demanding what it wants in terms of critical minerals – but pressing home its advantage may serve it less well over the long run.

4. Avoid leaving security planning to later: that can invite trouble.

The US has so far avoided giving Ukraine clear security guarantees in return for access to its critical mineral revenues. That appears part of a strategy to encourage Europe to step up its military involvement and generally to try to disengage the US from messy foreign wars. Instead, the US administration has suggested that the US’ proposed involvement as a commercial partner in Ukraine’s resources sector should in itself provide good security deterrence – discouraging Russia, for example, from breaching the terms of any peace deal with grabs for more territory.

The experience of resource assets in other unstable regions suggests this may be optimistic thinking. Particularly if the US-Ukraine critical minerals deal begins to result in big profits in regions of Ukraine close to Russian controlled territory and with only light-touch security, Vladimir Putin may find it hard to resist wanting more.

Many foreign-backed resource projects in unstable regions have struggled in their early years to predict how the security context might evolve, underestimating how their commercial success at a later stage would attract attention from different violent groups. Some have then been forced to overcompensate, turning themselves into highly defended compounds, incurring big security costs and weakening their ability to build local relationships (see here and here for examples).

On a geopolitical level, likewise, there are many past cases of leaders of militarily powerful countries succumbing to the temptation to grab a slice of valuable natural resources located outside their current borders. Examples include Saddam Hussain’s invasion of oil-rich Kuwait in 1990, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro’s threatened annexation of an oil-rich region of neighbouring Guyana in 2023, and Rwanda’s current reported backing for rebel incursions in the mineral-rich eastern DRC.

President Putin certainly has past form in brushing aside previously-agreed borders. In this respect, it may be better for the US to at least begin to plan now for security provision around its joint critical minerals projects with Ukraine, whether the security is provided by Ukraine, Europe or from US funds. This could be the only way to head off bigger problems down the line.

5. Consider ‘the deal’ as a potentially decades-long process.

There may already have been an evolution in US thinking over the last few weeks from a transactional, demand-all-we-can-get approach to Ukraine’s minerals to a more of a ‘win-win’ mindset. As already noted, this shift will need to be taken further. But mindsets also may need to change gear in terms of timeframes, and the need for strategic patience and adaptability.

The history of the most successful resource collaborations between countries, or between countries and companies, is one of periodic renegotiations of original deals over the space of years and decades, as each side listens and adapts to the other’s evolving situation and needs. China’s current position of strength in critical mineral value chains results from a multi-decade industrial strategy and cumulative process of interaction and diplomacy with different mineral-rich countries.

A good example of a mature, successful collaboration between a global company and mineral-rich country is the half-century-long relationship between De Beers, the diamond firm, and Botswana, the source of many of its stones. The deal between the company and the country has been periodically renegotiated over the decades, generating increasing benefits for Botswana while still also serving De Beers’ interests.

On an even grander scale, the US’ historic strategic relationship with Saudi Arabia is another example of a successful, albeit often controversial, long-term international partnership focused on resources (in this case oil). This partnership has had to adapt dramatically to survive over the years, shifting from outright US control over Saudi oil production for several decades from the 1930s to a now broader state-to-state collaboration focused on energy security and strategic and military cooperation.

Given the current bad blood between Presidents Trump and Zelensky, the apparent imbalance of power between them, and the fraught and destabilising daily news cycle, any such mutually advantageous, long-term partnership between the US and Ukraine may seem far off. But it is at least not impossible to imagine an eventual future in which Ukraine’s critical minerals comprise an important part in western manufacturing value chains, and both Ukraine and the US reap significant economic and geopolitical benefits as a result.

In short, amid the shouting, and short-term transactional focus, there is a genuine ‘win-win’ to aim for. The big challenge is that it requires vision, patience, listening, and adaptability on all sides to get there.

Cover image: Iron ore quarry in Ukraine by igorbondarenko, December 21, 2023, 1859727785

Image 2: “Anti-terrorist operation in eastern Ukraine (War Ukraine)” by Ministry of Defense of Ukraine is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.